altered reality

there goes the neighbourhood

fogs i have known; one i have loved

You’re driving in the pea soup of the Yorkshire moors, certain you can hear those puppies of Baskerville at every turn—not that every, or any, turn can actually be seen—and then, after some miracle of finding the way back to where you’re staying you hear the news that the roads in the moors have been closed all afternoon due to especially bad weather.

In Newfoundland, you sit on the rocks right at the edge of the sea with a picnic dinner and a bottle of wine, when out in the distance, over the water, comes a mist. At first it’s pretty, ha ha, you say, look at the pretty mist… But you’re from Ontario and you have no idea. You think you will continue sipping your wine, that the mist will just stay where it is, but then you notice it’s moving or, more accurately: ominously marching your way. In seconds it travels what appears to be miles, obliterating the landscape as it goes. Poof! Now you see rocks and trees and ocean. Now you don’t. And you can’t help thinking you’ll soon be next. You grab your picnic and head for the shelter of your B&B, which is much further away than you’d like at this point—and The Thing continues to come. The air is suddenly icy and within moments you can see nothing. It’s like being invaded by some silent invisible army. You sit on the porch, grateful for your wine, because if this is the end of the world at least you have that. Later, in the B&B, you tell the lovely owners about this extraordinary event and the way they look at you… well, you have never felt more like you’re from Ontario.

The ferry from Victoria to Vancouver. It’s your first crossing and you’re lucky, the ship is almost empty, you can sit where you like. You look forward to the view; you’ve been told it’s spectacular. But boo, there’s heavy fog. For a while you worry how the ship will find it’s way, you become tense and slightly pissed off about the non-view. But then something about all that nothingness turns comforting. The world seems bigger somehow precisely because you can’t see it. You write and sketch and take hazy photos. You don’t even like boats but sailing through this cloud is one of the most relaxing things you’ve ever done...

if you can keep your head…

my day, in food and words

It begins with a haircut.

Not at the cheap place where you can just walk in without an appointment, where I ususally go—essentially a unisex barber—but to my old, more expensive, hairdresser who I used to see when my hair was long and didn’t need cutting every twenty-five minutes. It still feels like I’m having an affair, this new place; I’ve never accepted that I really left the old place. Just taking a break. I go back a couple times a year for a decent cut, a template for the uni-barber to follow. A little unconventional but it seems to be working for all three of us.

It’s a day of errands and appointments. There is the usual traffic. A bus pulls in front of me at a dangerous angle; I consider making my feelings known but the sun is shining and it’s easy to be nice, so I keep my hand on the wheel.

A woman, sixties, stout in a pink house-coat with permed hair the colour of cardboard, smokes on her balcony, and later, in a different part of town, there is a man, also in his sixties, trying to get on a unicycle. I round the corner and never know if he succeeds.

The appointments and errands go on and soon it’s late afternoon and I haven’t eaten and I know I won’t get any work done even if I return to my desk so I decide to take myself out for a bite, treat myself to that place inside the art gallery, but it’s closed. The gallery itself, however, is open and though my stomach is growling the exhibit draws me in: William Brymner, his own work and that of his students, Prudence Howard, Morrice, A.Y. Jackson, et al.

The Quebec paintings are always easy to spot—all church steeples and snow. Even the houses have churchy elements, even the log cabins alone in their forests of birch— especially the cabins.

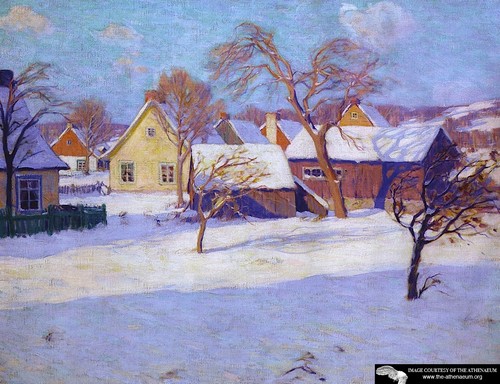

In Clarence Gagnon’s ‘Winter, Village of Baie-Sainte Paul’, a wind blows on a sunny afternoon. Lunch has been eaten, slabs of cold tortiere and glasses of cider. The dishes are done. The men have gone back outside, the children too. It might even be a school day. Inside the slope-roofed houses women breathe on the glass as they look out onto frozen gardens, broken fences and knee high drifts of snow.

I like the idea of painting en plein air and vow to do some soon. Pourquoi ne pas en hiver? Well, maybe just a quick sketch…

I still haven’t eaten so I stop at a deli on my way home, the one I used to take my mum to on errand days when she’d come with me for the ride, staying mostly in the car, especially if I parked in a sunny spot. She was like a salamander then. I’d stock up on her favourites: blocks of smoked bacon to slice or grind with garlic and eat with fresh rye bread, brandy filled chocolates, sauerkraut and a bag of pfeffernusse—a spicy cake-like cookie. I’d always buy one square of ice-chocolate from a box near the cash register—creamy milk chocolate that feels cool when you eat it. She wakes up when I open the door and all groggy wonders where we are; I hand her the chocolate and like a child, she brightens immediately, fumbles with the gold and turquoise foil, pops the whole thing into her mouth. I hear her dentures clatter and soon she begins to sing crazy old songs about chickens and underwear, songs I’ve been listening to all my life. I tell her I got the smoked bacon, and she hoots, says let’s go home and eat!

That was then.

The last few months of her life, after the stroke, she was in a nursing home and for a while she still ate the bacon and the rye bread, the chocolates and cookies. Surprisingly, it wasn’t this stuff that killed her, in fact it’s what kept her going, all that was left. When nothing else mattered, the bacon was still a small joy, some connection to better times—she always talked of home when she ate it, the mountains, her mother; it even made her sing occasionally, even in that hideous room.

The chocolates and cookies went first, and when one day she said no to the bacon and bread, I knew the last corner had been turned.

All this comes back to me as I stand in the delicatessen, choosing meat for a sandwich, my stomach still growling.

I buy the meat. And a bag of pfeffernusse, a block of smoked bacon, which I’ll put through a meat grinder with garlic, salt and pepper. I buy sauerkraut and brandy filled chocolates. I want to buy more but I leave it at these things, some of which I don’t even like, it just feels good to place them in front of me on the counter. And then even better to carry them outside into the sunshine.

I open the car door, set the bag down on the passenger side. Only the square of chocolate is missing.

instructions: ‘how to exist’

what happened to jumping in?

I’m watching a woman vacuum leaves. She’s strapped on a sort of large black bag, something like what newspaper boys and girls used to carry on their rounds, before their parents started driving them. The bag is attached to a long, fat nozzle which she points at the leaves she’s raked into a pile. At first things seem to go well enough. When the pile is sucked up she turns off the machine and empties the black bag into a paper sack intended to be put out onto the curb.

can a guy get a little privacy?

a new category is born: *judy sightings

*Judy: a long-suffering (make-the-best-of-it) dame of a certain vintage, usually attached to a male of a similar vintage.

~

MORNING AT TIM HORTON’S, PENTICTON

Judy, shoulder length brassy blonde hair, wears a white blouse, black slacks, name tag—My name is Judy—pale blue cardigan. Sits with sturdy, well fed man in race car driver sunglasses, football shirt, jeans and gold windbreaker. They begin their day in silence, blowing synchronicity onto their tea.

DEPARTURE LOUNGE, KELOWNA AIRPORT

Judy in crimson cardigan, black polyester tee, black purse rests on knees and what look like long johns poke out from the bottom of black slacks. Bare feet in black shoes. She files her nails beside a guy, a slow but incessant talker, in navy cap, navy golf shirt worn and faded, khakis, white socks, black sensible-sneaker-shoes. They both wear eye-glasses. Both have small carry-ons; hers, striped, crimson, white and black; his, royal blue with red trim. She rarely speaks and then in a high pitch, like a child, like her voice is seven decades younger than the rest of her. He answers in a way that whatever she has said, he’s setting her straight. He has all the answers. He knows. She listens, continues to file her nails, sometimes swings her feet that, if she turns her toes up just a titch, don’t quite reach the floor. He keeps his firmly crossed and locked—right mid-calf resting on left knee. She has been filing her nails beside him for 50 years.

CALGARY AIRPORT

Judy, short and squarish with grey hair, also short and square, glasses, maybe some hip issues, ortho type white sneakers, limping along the concourse with her guy, each pulling trollies, he in a lumber jacket (red and black), she stopping, making him stop too, placing a raccoon hat, grabbed from a display, on his head. Too small. She laughs. Hat clerk laughs too. Guy smiles, shakes his raccoon’d head. She is a riot everywhere they go.

the first time

It really doesn’t matter how good or not the first time is—it’s usually memorable and that’s enough. My first was James Michener. Well, not technically the first. There were plenty before him if you want to go back to Dr. Seuss. Then Lucy Maud and those Grimm Brothers, Heidi and Black Beauty, E.B. White, and Nancy Drew—who I used to think actually wrote the books; I was somehow oblivious to Carolyn Keene’s name prominently placed on all the covers. I’d love to know who I thought she was.

There were others, obscure names and stories I’ve long forgotten, picked up at the library or found among the slim pickings on my family’s shelves. But it was James that was the real first, the one I found myself opening and not being able to shut until it was done. The first time I went all the way in one fell swoop.

It happened under a tree.

It was summer. I was twelve. I had a bike. This was in the days before people got driven anywhere; when your parents could have cared less where you were as long as your room was clean, the dishes done, laundry hung, house vacuumed, garbage taken out and you were back in time for supper [‘cuz that table ain’t gonna set itself].

It was also in the days before the invention of plastic. At least in the shape of water bottles. People, everyone really, used to go places, everyplace, without water. It’s a miracle we all survived when you think about it now.

In any case, there I was on my bike in summer and it was hot. Very very hot. I rode across the canal into the country where the orchards lived and swiped a few peaches. And then I took those peaches to a small park—no, it wasn’t a park, more like a place for cars to pull over and check what the hell is making that rattling sound in the trunk. It was a small grassy space; there were trees, shade. Peaches. And James between the covers.

The book was The Fires of Spring. I remember the beginning best, how a little boy and his grandfather lived in a poorhouse, happy but poor, you know the type. The old man, beloved by all, died, leaving the little boy on his own. So he joined the circus, the way you do when your poor, beloved grandfather dies, and saw unspeakably exciting and horrifying things and possibly fell in love or lust or confusion. It gets foggy at this point. In fact, I remember very little and what I do recall may or may not even exist in the book.

Who cares. The story isn’t the point. The feeling is the point and no one and nothing, including the actual plot, can erase the feeling of laying on that small slice of cool grass on that hot day, illicit peach juice dribbling down my chin onto James’ pages as I turned them one after the other after the next… all afternoon.

It was the book that showed me, in ways I can’t recall, the power and the magic of words. It wasn’t necessarily the best I’d ever read, I just remember it that way.

Recently, when Peter and I spend a weekend in Niagara, we find ourselves near the grassy place. I ask him to pull over, tell him about James…I spare him the details.

He finds my nostalgia quaint, smiles, stays in the car while I walk around. Which tree was it? This one, that one? I study branch formation, proximity to the road, until it occurs to me that where matters as little as the storyline. What matters is I”m suddenly breathing deeply, smiling, shoulders drop and I’m twelve, in yellow denim cutoffs—because I’m the only kid I know who doesn’t own blue jeans—lying tummy down on grass, surrounded by peach pits and so engrossed in a book a whole day goes by without me noticing. Best of all, I am not even slightly aware of how I will remember this day, for possibly ever.