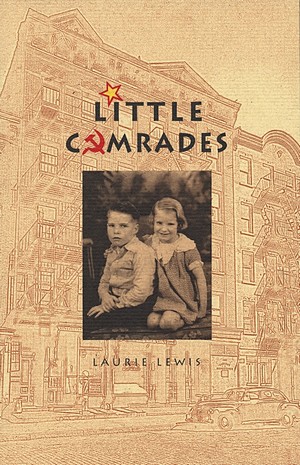

I don’t know of (m)any other memoirs about growing up in a Communist family, in Canada or elsewhere, or why such an account might be scarce. The habit of secrecy perhaps, not wanting to name names? Whatever the case, in Little Comrades, Laurie Lewis has chosen to leap where few have leapt.

And I’m pretty sure the result is not what  you think.

you think.

There is a strong-willed mother, a departure from the west to Toronto, another to New York City, an abortion in the 50’s, alcoholism, The Great Depression (and how to survive with style; the lost art of great style is everywhere…), the war, few women’s rights (women could be ‘legally bedded’ at age eighteen). There is Kill a Commie for Christ, racism, sexism. And secrets. Always secrets.

There is also Mulberry Street and her love of NYC. In fact, despite all the ‘isms’ of the era, it’s love that comes out strongest. For her mother, for freedom, for the people who helped them, for Sol whose loud, robust family, culture and food she craved after a fairly white-bread upbringing that didn’t encourage independence, creativity or opinions outside party lines.

“My father had written a letter to the Communist Party Central Committee… so they’d know that he had given his wife permission to leave him.”

While describing the larger issues of the day, the unorthodox turbulence of her home life and the difficulties of being a little comrade in general, Lewis manages to maintain a voice appropriate to her youth and still-innocence. Describing a visit to an avant garde cinema as a young teen, Lewis writes: “The theatre showed ‘foreign’ movies. Sometimes British, sometimes European, with sub-titles, so you’d know what people were saying.”

Her writing is beautifully precise, often tactile, so that the reading at times feels a little like wandering about with the author as she confidently points things out that, pretty soon, we can also see just as plainly.

I’m delighted to have read this book (which ends in 1952) and have already purchased the sequel: Love and All that Jazz.

So without further blather, and with enormous thanks to the author, here is (at) eleven with Laurie Lewis:

♦

1. The first question I always ask in this series is what literary character did you relate to as a child. Given your unusual childhood, I’ve never been more curious to know the answer.

LL—I’m afraid I can’t tell you the answer to this. Perhaps something will come to me as I get further along into this process.

2. What were you reading at fifteen?

LL—Oh, that I do remember clearly… two very different things: In my early teens I was very interested in math and science, and one of the books I received (from my father, a great surprise) was Mathematics for the Millions, by… how good is my memory? Yes, Lancelot Hogben, or a name very much like that. I could probably ask Mr. Google right now and get the right answer!! [Yes!! He’s there, and the book is there, still in print! Amazing!] The other thing I was reading was Dorothy Parker, who had a new collection of short stories out just then, 1945. I remember reading them to my mother when she was ill. She was a smart sassy woman speaking her mind. Very avant-garde. What a role model! And Robert Benchley, Ogden Nash, James Thurber. The New Yorker writers of the period… my mother’s choices, of course. Elizabeth Barrett Browning. And I remember my very first Virginia Woolf story, although I don’t know how old I was, perhaps younger than 15, I believe. “Flush”.

(I should say here that my mother didn’t believe in “children’s books” as such. She grew up in a working-class home of a skilled carpenter from England, with a room full of Dickens, which she regarded as books for children, since that’s what she had read.) To my own daughter, I read Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, of course, and Mary Poppins. The Mary Poppins movie came out shortly after she and I moved to Toronto, when Amanda was 8 years old. I vividly remember that when a school friend asked her if she had seen the movie, she told her, “No, but I’ve read the book.”)

Pre-teen poetry: Vachel Lindsay (a sort of pre-beat poet. Sort of “tribal” as I recall.) Emily Dickinson, of course. Robert Burns from the Scottish side of the family.

3. Did it ever occur to you that it wasn’t the norm for children to be as aware politically as you were? Looking back on it, how did this awareness, this lifestyle, affect friendships? Did you feel different from other children; did you see the difference in your family?

LL—I think you are perhaps not correct in thinking it was not the norm. Those were intensely political times in the history of the world, both during the Depression and World War II. During the “Great” Depression politics were part of people’s lives, I think. Not only mine. (In the way that the Vietnam war was a part of the lives of Americans during that difficult time. And everyone had an opinion.) Extreme, extreme(!) poverty creates its own awareness. Yes, I was generally aware of how it might have affected friendships… One of the pieces I wrote about, called “Lumpen”, was about a potential friendship that was out of bounds because the parents were “lumpen” (i.e. non-political working class – non-politically aware). And I remember being invited somewhere by a little girl of about my own age, a girl who put on a pretty dress every Sunday and went to some sort of party. Sunday School. I asked my mother if I could go, and she dressed me up in my best dress, my school dress. (Perhaps you know that a poor girl in those times might have two dresses. One for school and one for play. No jeans, or anything like that, of course.) I’m sorry to report that I was asked to leave when I, at about six years old, questioned the story of Adam and Eve (since I knew about Darwin).

Also, I became very aware of a class divide. We were definitely not “middle class” in either our economic circumstances or our outlook on life. I think the children we now call “disadvantaged” (not “poor”… we never say that anyone is “poor”!) are very aware of a class divide, regardless of what it is called. I assume it affects their friendship patterns. To some extent I think economic disparity affects our friendships at any age.

4. In the New York City chapters, while you were often worried, knowing that you or your mother might at any time be questioned, or worse, for communist connections, and despite the many moves and difficult encounters, I sense that the city offered you a new kind of happiness and freedom. Was this a turning point in your life? Would you say your mother experienced something similar?

LL—Yes, certainly there was a kind of freedom. The important thing, especially for my mother as a newly-separated intelligent and creative woman, was that the city was wide open for anyone who had talent and drive, and she had both. That’s not quite the same thing as “happiness”, but I’m not sure what that word means. I was a young teenager. Certainly I had more opportunities than I would have had in a small town, or in a “provincial” city like Vancouver. There was freedom from the coercion of the domestic politics of power, and a more cosmopolitan, more diverse “ethnic” environment. More people from more places, not the homogeneity that was Canada at the time. (A tad more financial security would have helped both of us, of course.!) Yes, certainly it was a turning point. When I got my first job, as an usher in the movies (they had them then!), I was terribly proud of myself. I could earn a living!

5. Also, those chapters so beautifully and vividly describe a city that it’s said no longer exists. What was it like to revisit in the writing? And what are some of the more regrettable losses?

LL—Yes, we revisit places and “social environments” when we remember. I don’t think I have ever tried to compare the old and the new… Well, yes, I suppose I have, but what can I say? The buildings have changed, the people have changed, the way of life has changed. And I have changed. Especially now, in my old age, I am more aware of the vast spaces where people I knew, people I loved, do not exist any more. That is the most regrettable loss, the loss of those we loved, cared for. The rest is just history, just “stuff”. Beat was beat; hip was hip; hippy was hippy. So vastly different! And what is cool today will be passé tomorrow.

6. Despite being surrounded by writers in your family, and in your publishing career, you didn’t begin writing seriously until your sixties. This rather late start not only makes you an inspiration to many late starters, it also gives you a rare perspective, i.e. how differently, if at all, might the story of Little Comrades have been presented had you written it at, say, age 35 or 40?

LL—A very tricky question. I’m not sure how different the story would have been, but if I had written it then, when communism and therefore anti-communism were still very powerful and antagonistic forces in the world, the reception would undoubtedly have been different. Communism, these days, is looked back on almost with nostalgia. (Not the specifics of Russia, of Stalin, but the economic principles.) As far as I, personally, am concerned I think it’s important to say that age gives me a kind of power, through the freedom to say whatever I damned please. This is a power that perhaps young people with young careers rarely really have. And I certainly felt the freedom to present my story with – well, of all things! – the dignity it deserved. I think I was aiming for something like social history, told through the mind of a child.

7. While still in high school, you had an affair with a man that resulted in your getting an abortion. The affair ended and a few years later you were surprised to see “a new and handsome face” appear in Hollywood movies. “That same face with the high Greek cheekbones, the dark eyes, artfully dishevelled black hair. His name? Yes, it could be a good Anglicization of the one I remembered but never spoke.” You tell us that he eventually became a director and married a ‘10’… all wonderful clues for what is a wonderful parlour game… Was this a promise to the man or a promise to yourself, not to reveal his name?

LL—I am merely being cautious. Two things: First, I can’t be absolutely sure that’s who it was. When I asked Mr. Google about him, the early bio made me a bit unsure. And if I had ever done more than hint, I could have been open to a suit for libel or slander. Probably because of my childhood experiences, I think I tend to be careful about keeping my activities legal. I’m a trifle paranoid, perhaps.

8. Your memory for detail is extraordinary, adding rich layers to the story, tapping various senses. That you recall people, how they looked, what they wore, what they did for a living, a pawnshop window… What was your process in getting ‘back there’—was it photographs, conversations, general research, letters, all of the above?

LL—I wish I had had letters, photographs, etc, but I didn’t. But I think memory is quite wonderful. My “chicken soup” theory of memory says: The first time I ask my memory about something, there’s almost nothing in there. There’s just sort of a weak chicken broth, warm and salty. The next time I go looking into that memory, there are a couple of peas, maybe a piece of carrot. And so it goes. Every time I look, there is more in that memory-space. [I think recent research shows that the soup in which the synapses operate between the dendrites must be sort of re-assembled, reconstituted, into the memory.] And some of it is pure deductive invention: for example, in a story about my aunt getting married I have said she wore a blue dress. Well, what do I really know? I don’t remember, but the dress wouldn’t have been either black or white. Nor red or pink or purple. Because they were Scots, it would have been unlikely to be green. Given the years of the forties, the colours were apt to be muted and “feminine.” All of that, for me, equalled a light blue.

And just because it’s a memoir doesn’t mean you can’t make things up! I mean, I am a writer! How much do I actually recall of what was in the window of the pawn shop? Two out of five things? One thing? But once I have written it, it becomes true for me, and I can see the window very clearly.

9. You had a close relationship with your mother, who comes across as a very independent woman for her time. She lived an unconventional life in many ways, not the least of which was leaving your father and giving you the choice of staying or coming with her. Also her work with the Communist party, the risks that involved and the lifestyle it required. Yet at some point it became clear to you that you had different values and ideas about lifestyle. How difficult was it to admit this to yourself and to become independent in your own way?

LL—She was a very independent woman for any time. Most of that was, I think, an independence formed by the combination of pride and desperation. She had some pride in herself, some idea that she had a mind, that what she thought mattered, and she was desperate to get out of a bad personal situation even if that put her into a desperate economic situation. In my mother’s time, if women were desperate to leave their husbands, they usually had another man to help them out… to help them get out, I mean. So then just, a few years later, we were two more-or-less young-ish women living together… when I was 18 and she was 38, for example. We really needed our own spaces. Perhaps the differences you mention – values and lifestyle might have had more to do with the simple matter of generational differences. And the number of years between the generations was much smaller than it is now, thanks to the easy availability of birth control in North America. All young people, male or female, have different outlooks on life than their parents have. I know that some may make choices to stay closer to the zeitgeist of their parents, for whatever reason. In the 1960s, rebellion was in the air, change was in the air. I was just a few years ahead of my time, as Ellen (my mother) was a few years ahead of hers, always.

10. It feels like a life of many secrets. You say that even today there are names you “won’t name”… people who were once involved in the Communist party. Did you have to think twice about writing this book?

LL—In the beginning I didn’t know I was writing it. I was just writing stories about what I thought I knew. When I began to write some of the early family stories, my mother said, “It wasn’t like that”. We each have our own truths, the things that we believe to be the truth of our lives. And we can’t let anyone else decide for us what it’s okay to reveal. My mother’s memoir, “Always and After” is much more cautious politically. I don’t think mine is a broad tell-all memoir, full of scuttlebutt. I was focussed on specific areas of our lives: politics, gender, personal growth, insight. By the time I had finished writing Little Comrades my mother had died, and so there was no one to tell me I had done it wrong. (And I didn’t name names, as you know from question 7.) Also, I probably still have lingering fears, some paranoia, from the McCarthy era, and so, even with my general “mouthiness” I have some caution in me. I don’t feel that I have said anything truly dangerous, either to myself or to anyone else. (And everyone’s dead now.)

**

I will go back now to the first question, which literary character I related to:

At the end of this, I have come back to the beginning, and what has come to me is Heidi: homeless and hungry. What a surprise that is to me!! Thank you for asking. I think this is the secret of my childhood, Heidi. I could cry, even now, for that poor little girl. But I think I will go out to dinner instead.

11. Choices:

Coffee or tea? Tea in Canada, coffee in Mexico.

Poetry or song? Poetry

Sweet or savoury? Savoury

Dessert or Appetizer? Appetizer

Winter or Summer? Summer

Pen or Keyboard? Keyboard, although as a graphic designer I flirted with calligraphy.*

Bicycle or Canoe? Bicycle… it’s in the garage right now with a flat tire.

Ocean or Lake? Lake

Morning or Night? Morning

Film or theatre? Theatre

The Ten Commandments or Exodus? ha ha ha… Exodus.

* Here’s another note about Pen or Keyboard: Keyboard, although as a graphic designer I flirted with calligraphy, and so the “pen” has artistic value rather than any writerly presence. Whereas, I learned to touch type when I was 17, and so I firmly believe that my fingers know stories that they are eager to tell me. My fingers do their work, and then I read what they have said. There is a direct line from a part of my brain into my fingertips.

Matilda’s Menu for Little Comrades:

Bacon Sandwich

Alymer Soup

Blintzes

Prosecco

As is customary with the (at) eleven series, a meal of my choosing—appropriate to the book—follows the Q&A, because… “Eating is our earliest metaphor, preceding our consciousness of gender difference, race, nationality, and language. We eat before we talk.” ~Margaret Atwood from The Can Lit Food Book

Happy Reading, and bon appetit

◊♦◊

Laurie Lewis is a Fellow of Graphic Designers of Canada and is editor emerita of Vista, the publication of the Seniors Association in Kingston, Ontario.

Laurie Lewis is a Fellow of Graphic Designers of Canada and is editor emerita of Vista, the publication of the Seniors Association in Kingston, Ontario.

She began writing in 1991 after retirement. Her written work has been on CBC and has been published in Contemporary Verse 2, Queen’s Feminist Review, Kingston Poets’ Gallery, Queen’s Quarterly, and The Toronto Quarterly. Her memoir, Little Comrades, was published by Porcupine’s Quill in 2011 and was named by the Globe and Mail among the Top 100 Books of the Year. A second memoir, Love, and all that jazz, was published in 2013 by Porcupine’s Quill. She is currently working on a collection of essays and stories about age, but is not persuaded that the title “Mouthy Old Broad” will have much commercial appeal.

(my vision of Ian; courtesy of wikicommons)

(my vision of Ian; courtesy of wikicommons)